The Swedish construction sector is in a major transition at the moment. The step-change we are aiming for is to radically lower production costs so that the construction price index approaches the retailer price index. There’s a post here that motivates why we’re so eager to change. In short, contractors are aiming to move up in the value-chain in order to tip the balance of project types from build-to-specifications projects to more design-build. In order to do that, we are developing quite a number of different platforms which help us offer flexibility but with fewer resources used. The idea is to standardise whatever does not interest clients (for example, we do not have to design new wall-to-floor interfaces every time) and leave open what is important for the client to be able to choose. In order to be able to do that rationally, we might even pre-package optional alternatives. Suddenly, we find ourselves discussing about a company that develops products. Ad-hoc becomes the anomaly.

The NCC AB sports hall is a product, thirty examples of which have been built in various configurations.

With product come a number of more or less more usual platforms, for example:

- Technical: Gadgets. Engineering solutions of common problems.

- Production: The making of. Methods for to build the technical platforms.

- Supply: Made in. Who to buy from. How to collaborate. When to invite new tenders. How to measure success.

- Process: Activities. What to do. When to do it. What to ask the client. What to deliver.

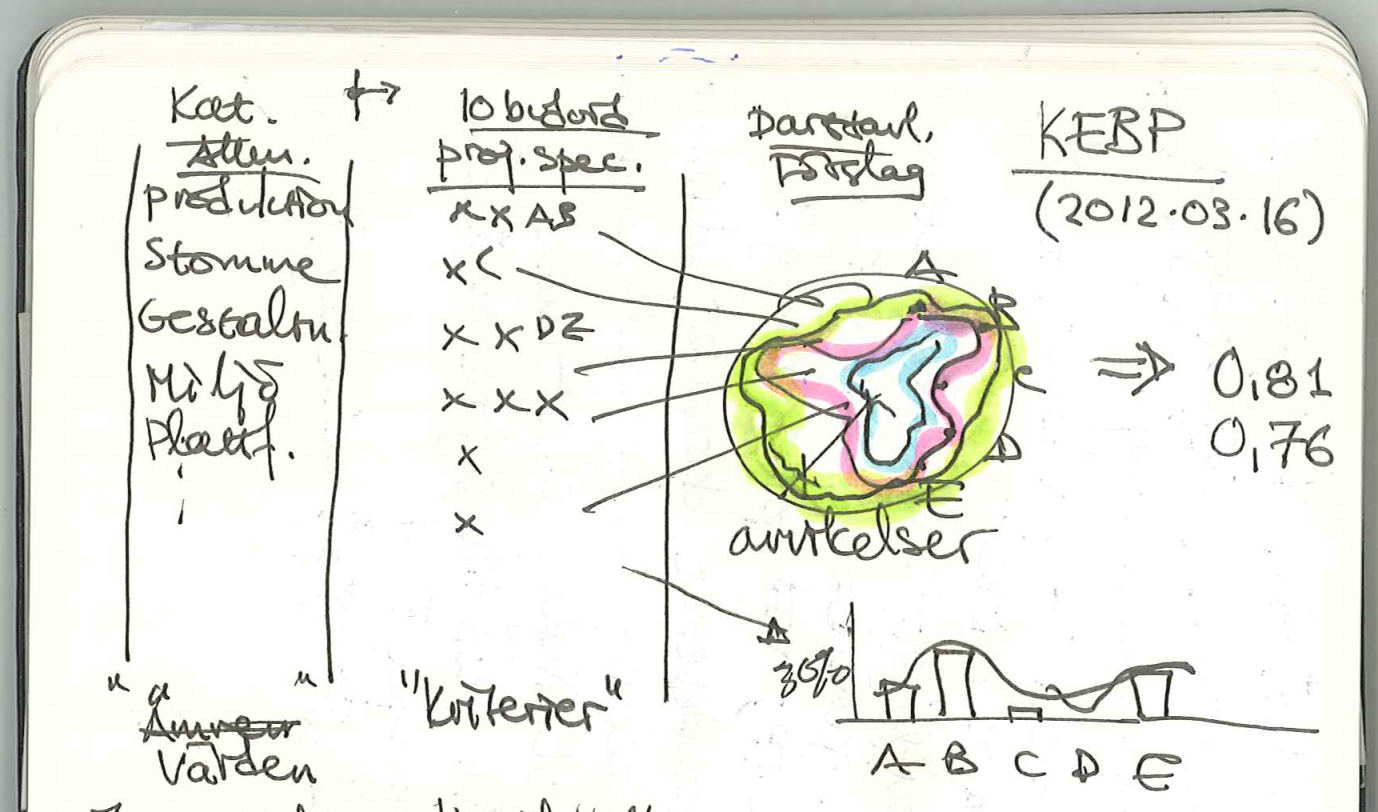

And it works too. Here’s one example of that. Process platforms work brilliantly for the renovation and refurbishment sector by the way. But let me give you a very fresh example of what I’m talking about. My colleagues and I are working on one small piece of a process puzzle. We work for a contractor with a strong ambition to be a systems integrator. So we are thinking about how to best communicate our technical platforms to architects, instead of sending them as wordy, dry and biiiig pdf documents over email. Could we use our own successful buildings as templates? Maybe. The key issue is what constitutes a successful building. Depends on who you ask, right? Right. The image below is from a meeting we had on that today. It addressed a collaborative procedure we are working on for a developer, contractor and design team to come together on how well a draft building lives up to our expectations.

First sketch from today on the basic lay-out of a decision-making process platform in design.

This procedure would be requirement-based part of a process platform for design. If we pull it off, it will give a number of themes (left column: production, structure, aesthetics, environment, platform adherence and so on). For each project, the team would define the ten commandments – the ten most important traits of the building. That’s the middle column. (Commandment A could be under Production: Bathroom pods to only have interior walls. Commandment B could be under Structure: free spans no longer than 6 metres.) And all members will grade each commandment after its importance.

Enter the architect with a new building draft. At a meeting, each member of the team grades the draft after how well it lives up to each commandment. There is then a nice little spreadsheet we’ve developed that makes it possible to see in a spider chart – in real time – what the group thinks about the draft. It is possible to highlight the mean (pink), minimum (blue) or maximum (green) votes, so we see where the group agrees and where we disagree. That’s the diagram to the right. If you get to motivate your three on structure, we’ve seen that discrepancies are not only are highlighted but also mitigated by discussions.

Finally, the spreadsheet gives a final compliance number (the numbers to the far right) for each draft we process. OK, so we don’t expect anyone to use them as the final word in any way. But they are very useful to highlight the consequences of the requirements we state we have and the assessments we’ve made. They are also useful for seeing how well we meet our own requirements over time and over the course of a project. Can we motivate why we put a draft down? In short, this process makes us put our money where our mouths are. In the open.

That’s just one example of a process platform procedure. We have quite a substantial number of such procedures to develop to complement the ones we have. It might seem like a tall order, but it’s not brain surgery. It’s just a matter of deciding as a company to keep to a predetermined order of business.

Here’s the process, in brief. First get under the skin of your client and think ahead what will work based on their drivers. Note: you likely have some homework to do there. Then develop products that suit your image of the clients’ needs to complement your regular, more traditional methods. Make sure they are flexible from the clients’ viewpoint and rational from your viewpoint. Note: that’s harder than it sounds if you want to make money while doing it; better read a book or two. Then use them; build a house. Get feedback. Measure your success the same way your clients measure their success. Draw conclusions. Improve. Start over.

That is our step-change.

Images: Top:Sports hall, copyright NCC AB. Bottom: Sketch book by Dan Engström, Creative Commons by-nc-sa

Facebook

Facebook

Lämna ett svar